Sunday, July 3, 2011

Thursday, September 23, 2010

En, Ensi and Lugal

We have to discuss 3 titles,

Lugal [Gal-Lu2]

Sumerian for "great man", the Akkadian equivalent is read "sharrum" (king);

En [En]

close to priest-lord and

Ensi [pa-te-si/ensi2]

conventionally translated as city ruler

The difference between En and Ensi:

Jacobsen in his 'Toward the Image of Tammuz' (1970), p.384 n.71, explains that Ensi[g/k] when attested at all, "seems to denote specifically the ruler of a single major city with it's surrounding lands and villages, whereas both "lord" (en) and "king"(lugal) imply ruler over a region with more than one important city....the ensi[g/k] seems to have been originally the leader of the seasonal organization of the townspeople for work on the fields: irrigation, ploughing, and sowing. " The author assigns the meaning of the word as "manager of the arable lands" and comments that it would not be difficult than, to see how the ensi[g/k] could gain high political influence in Early Dynastic times.

Differences between Lugal and En:

In a JNES article Jacobsen/Kramer touch briefly on the differences between en and lugal (JNES 12, 179, n.41):

"The traditional English rendering [of en] "lord" would be happier if it had preserved overtones of its original meaning "bread-keeper" (Blaford), for the core concept of En is that of the successful economic manager. The term implies authority, but not the authority of ownership, a point on which it differs sharply from bêlum (Sumerian has no term for owner but has to make shift with lugal and constructions with -t u k u) , and it implies successful economic management: charismatic power to make things thrive and to produce abundance."

Lugalship (Nam-Lugal)

and

Enship (Nam-En)

(Adapted from "Fischers Weltgeschichte - Die Altorientalischen Reiche I "1965)

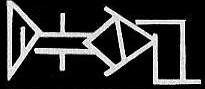

Lugal is the royal title "par excellence", like that known from the Sumerian king-list. Nam-Lugal is the kingship as a form of ruling. Lugal connected with a name is found first in Kish and Ur (Mebaragesi, Meskalamdug), but the combination of the signs

[Gal+Lu2]

is already known in UrukIII-Jemdat-Nasr-Time. Unlike the title Lugal and Ensi, the title En as a ruler title [with political as well as social powers] is only known from Uruk. Enmerkar, Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh are called "En of Kulaba" (Kulaba is a city district of Uruk) in the "hymn literature", also Meskianggasher, ancestor of the first dynasty of Uruk, and again Gilgameš [have the same title] in the king-list.

The statement of Lugalkingenešdudu (ca. beginning 24th century), "he owns the Enship (Nam-En) of Uruk and the Kingship (Nam-Lugal) of Ur" is a characteristic for the connection of En and Uruk. Only one time, at the reign of Enshekushanna of Uruk (ca end of 25th century) the title "En of Sumer"(En Ki-En-Gi) appears.

![]()

Epigraphically En is earlier attested then Lugal. The cuneiform sign is found in texts from UrukIVa, at the time of the archaic Sumerian "high culture". The personal name "The En fills the Kulaba", from archaic Ur, shows the high prestige of the title En outside of Uruk.

The title En as a title for a priest was often used in Ur (since Akkadian times). Here it is the high priestess of Nanna, city-god of Ur, who used the title. If the En of Uruk was a ruler with a female city-god, Inanna, the title En would necessarily be opposite in gender to the city-god.

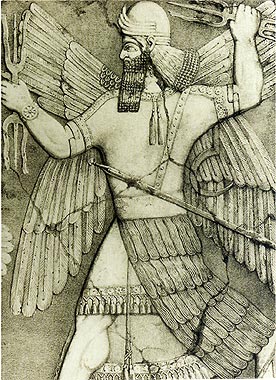

The En of Uruk-Kulaba was probably more involved into cultic functions then the Lugal, and so, the figure of the priest displayed in priestly functions on cylinder seals from UrukIV layers is to be identified as the En.

The politcal aspect of En only shows up in the stories of Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh. In cities like Ur or Girsu (the main city of the state of Lagash) the Lugal or Ensi didn't unify the highest cultic and worldly functions in one person from the beginning. Under Entemena of Lagash in Girsu there was a highpriest of the city-god Ningirsu, called Sangu who stood next to the Ensi. But this is a relatively late reference (end of 25th century).

*A classic note on the En is in Kramer's the Sumerians pg. 141, which states that while the Sanga was the administrative head of the temple, the En was the spiritual head of the temple who:

"..lived in a part of the temple known as the Gipar. The en's, it seems, could be women as well as men, depending upon the sex of the deity to whom their service were dedicated. Thus in Erech's main temple, the Eanna, of which the goddess Inanna became the main deity, the en was a man; the hero's Enmerker and Gilgamesh were originally designated en's though they may also have been kings and were certainly great military leaders. The en of the Ekishnugal in Ur, whose main deity was the moon-god, Nanna, was a woman and usually the daughter of the reigning monarch of Sumer. (We actually have the names of almost all, if not all, the en's of the Ekishnugal from the days of Sargon the Great.)

The Merging of En and Lugal:

Oppenheim calls the relationship between these two functions "complex" and "ill-defined" and referring back to Jacobsen 1970, pg. 144, its explained thats the distinctions between these roles is in fact sometimes blurred. "The related tendencies of kings and lords [en's] to strengthen their position by ruthlessly suppressing all rivals may be seen as a reason why in the various regions of Mesopotamia, as we find them in the epics, only one ruler, either a "king" or a "lord," is met with. With the regional unification of power in one hand goes a gradual merging of the various functions of the two offices, for all of them were needed for a community to thrive. The general warlike conditions would, in the case of the "lord," stress his powers of maintaining order and expand his police powers to full military scope. The "king" on th other hand, could not well disregard internal administrative and economic problems in his realm and would thus naturally came to assume also the "lord's" responsibilities for fertility and abundant crops. Thus the magic and ritual responsibilities were added to his earlier military and judiciary functions to form the combination so characteristic of later Mesopotamian kingship."

Ensi:

Further Perspective on En's:

Why the En makes such an appearance in Jacobsen's 1970 study "Toward the image of Tammuz" because apparent in referring to his note one page 375, n.32:

"The en's basic responsibility is toward fertility and abundance, achieved through the rite of "sacred marriage" in which the en participated as bride or bridegroom of a deity.In cities where the chief deity was a goddess, as in Uruk and Aratta, the en was male (akkadian enum) and attained, because of the economic importance of his office, to a position of major political importance as "ruler"." In cities where the chief deity was male, as in Ur, the en was a woman, (Akkadian enum or entum) and therefore, while important religiously, did not attain a ruler's position. Whether male and politically important as a ruler, or female and only cultically important, the en lived in a building of sacred character, the Giparu. Where the en was male and a ruler that building in time took on the features of an administrative center, a palace (see the epics of "Enmerker and the Lord of Aratta" and of "Enmerker and Ensukeshdanna"). Where the en was female this did not happen (Ur)."

In regards the Sacred Marriage, Jacobsen quotes a line from TRS 60: "At the lapis-lazuli door which stands in the Giparu she (Inannak) met the end, at the narrow(?) door of the storehouse which stands in Eannak she me Dumuzid.....The connection between the en and Giparu ["storehouse"] are made clear by the text as a whole, which, dealing with the "sacred marriage" shows it to be a rite celebrating the bringing in of the harvest. It describes first how Inannak, the bride, is decked out for her wedding with freshly harvested date clusters, which represent her jewelry and personal adornments. She then goes to receive her bridegroom, the en, Dumuzid, at the door of the Giparu- this opening of the door for the bridegroom by the bride was the main symbolic act of the Sumerian wedding, see BASOR 102 (1946 15- and has him led into the Giparu, where the bed for the sacred marriage is set up.......Summing up we may say thus that-at least in Uruk- the en lives in the storehouse, the Giparu, because the crops are in the storehouse and the en is the human embodiment of the generative power, Dumuzid or Amaushumgalanak, which produces and informs them."

Enheduanna and en-priestesses (and princesses):

The Gipar at Ur was uncovered by Woolley and was found to be a self-contained residence with kitchens, ceremonial rooms etc and even a crypt. The was the residence of the en priestesses and a bedroom was incorporated within the shrine which presumably relates to the Sacred Marriage ritual. J.N Postgate (1992 ph.130) relays: "The earliest En known to us was a daughter of Sargon of Akkad called Enheduana. She is also the most famous, since she is one of the very few authors of a Mesopotamian literary work whose name is known, but she was followed by a long line of important ladies, most if not all of whom were close relatives of the current royal family. Thus among others we find the daughters of Naram-Sin of Akkad, Ur-Bau of Lagash;, Ur-Nammu, $ulgi, (and probably subsequent Ur III kings),Ishme-dagan of Isin, and Kudu-mabuk - the last being sister of Warad-Sin and Rim-sin of Larsa. The memory lived on for well over a thousand years, when the last king of Babylon, Nabonidus, in a consciously traditional gesture made his daughter priestess of the moon-god at Ur."

The GAR.ÉNSI of Adab

gar.énsi (nig2-pa-te-si)

| Ruler | Title |

| Nin-kisal-si | GAR.ÉNSI |

| Me-ba-dur | Lugal |

| Lugal-da-lu | Lugal |

| Bará-hé-i-dùg | GAR.ÉNSI |

| Muk-si | GAR.ÉNSI |

| É-igi-nim-pa-è | GAR.ÉNSI |

[1] It is tempting to use the titles of rulers as a criterion for dating the Adab rulers, since the writing GAR.énsi looks like an archaism. But the GAR.énsi title in Adab was used consistently from the time of Nin-kisal-si down to that of E-igi-nim-pa-è, who would be closest to the Akkadian era.

Elsewhere, the same title was used by Sá-tam, Ruler of Uruk, during early Sargonic times. It therefore seems clear that the GAR.énsi title is not an archaism, but simply a (regional?) pecularity.Concerning the list i have drawn together above, i have not included in it the ruler named Lum-ma, despite the fact that his name is found on two votive inscriptions from Adab (A208 and A 217),one of which describes him as PA.SI.GAR. Lum-ma´s title was written PA.SI.GAR and PA.GAR.TE.SI, instead of the standart GAR.PA.TE.SI of the other Adab rulers; his title was never followed by the qualification "of Adab". These data would seem to indicate that Lum-ma was not a local ruler of Adab, but a ruler from another city who placed votive vessels in the E-sar temple.

[1] "Adab" by Yang Zhi

Friday, September 10, 2010

Of Historians & Sumerian Gods

The Historian and the Sumerian Gods

Thorkild Jacobsen

Journal of the American Oriental Society

Vol. 114, No. 2 (Apr., 1994), pp. 145-153.

www.jstor.org

www.google.com

Sumerian Gods and Their Representations

Irving Finkel; Markham Geller (Edtrs.)

Cuneiform Monographs, 7

While the majority of ancient Mesopotamian deities existed, under dual names, in both the Akkadian-language and the Sumerian-language traditions, with similar or identical characteristics, it is salutary and useful to focus on the earlier phases, which are, typically, "Sumerian."

In this volume are collected thirteen papers delivered at a symposium held at the British Museum on 7th April 1994, in memory of Thorkild Jacobsen, who died in 1993.

The editors have provided full indices (of words and, in particular, of gods, demons and temples) and a brief introduction (together with a dramatic photograph of the youthful Jacobsen in Iraq, as a frontispiece), but essentially the papers speak for themselves.

It is a credit to the inspiration of Jacobsen that the occasion and the choice of subject called forth a collection both so varied and so relatively coherent, since such is not always the case with conference proceedings.

Enki, Martu, Nanaya, and Nanna are the deities who happen to receive treatments at length, but the volume covers many other divinities and areas of the Sumerian mental world. ...

Journal of the American Oriental Society, The, Oct-Dec, 1999.

@ Google.com

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Ninurta: Patron of Kings

The God Ninurta

In the Mythology and Royal Ideology

Of Ancient Mesopotamia

By

Amar Annus

The present study has tried to show that the conception of Ninurta's identity with the king was present in Mesopotamian religion already in the third millennium BC. Ninurta was the god of Nippur, the religious centre of Sumerian cities, and his most important attribute is his sonship to Enlil. While the mortal gods were frequently called the sons of Enlil, the status of the king converged to that of Ninurta at his coronation, through the determination of the royal fate, carried out by the divine council of gods in Nippur. The fate of Ninurta parallels the fate of the king after the investiture.

Religious syncretism is studied in the second chapter. The configuration of Nippur cults had a legacy in the religious life of Babylonia and Assyria. The Nippur trinity of the father Enlil, the mother Ninlil and the son Ninurta had direct descendants in the Babylonian and Assyrian pantheon, realized in Babylonia as Marduk, Zarpanitu and Nabû and as Aššur, Mullissu and Ninurta in Assyria. While the names changed, the configuration of the cult survived, even when, from the eighth century BC onwards, Ninurta's name was to a large extent replaced with that of Nabû.

In the third chapter various manifestations or hypostases of Ninurta are discussed. Besides the monster slayer, Ninurta was envisaged as farmer, star and arrow, as healer, or as tree. All these manifestations confirm the strong ties between the cult of Ninurta and kingship. By slaying Asakku, Ninurta eliminated evil from the world, and accordingly he was considered the god of healing as well. The healing, helping and saving of the believer in personal misery was thus a natural result of Ninurta's victorious battles.

The theologoumenon of Ninurta's mission and return was used as the mythological basis for quite many royal rituals and this fact explains the extreme longevity of the Sumerian literary compositions Angim and Lugale from the third until the first millennium BC. Ninurta also protected legitimate ownership of land, and granted protection for refugees in a special temple of the land. The “faithful farmer” is an epithet of both Ninurta and the king.

Kingship myths similar to the battles of Ninurta are attested in an area far extending the bounds of the Ancient Near East. The conflict myth, on which the Ninurta mythology was based, is probably of prehistoric origin, and various forms of the kingship myths continued to carry the ideas of usurpation, conflict and dominion until late Antiquity.

Anyone familiar with even a smattering of Mesopotamian literary and religious texts can attest to the diverse representations of any divine or heroic figure in his or her numerous textual appearances. From the plethora of material and depictions arises the difficulty in responding to the inevitable question "Who was (fill in the name of your favorite divinity/hero) and what was his/her nature?" In the present volume, Amar Annus addresses this problem by compiling Ninurta material into a convenient assemblage. ....

Review

Tuesday, March 9, 2010

Ninurta & Kings

The notion of the king as the son of god held true only insofar as it referred to the divine spirit that resided within his human body. In Mesopotamian mythology, this divine spirit takes the form of a celestial savior figure, Ninurta, whose mythological role the Assyrian kings consciously emulated both in ritual and in daily life.

The Ninurta myth is known in numerous versions, but in its essence it is a story of the victory of light over the forces of darkness and death. In all its versions, Ninurta, the son of the divine king, sets out from his celestial home to fight the evil forces that threaten his father's kingdom.

He proceeds against the "mountain" or the "foreign land," meets the enemy, defeats it and then returns in triumph to his celestial home, where he is blessed by his father and mother. Exalted at their side, Ninurta becomes an omnipotent cosmic accountant of men's fates. It is this that the Assyrian kings emulated.

Hero!

Hero!

Terror-inspiring Dragon

Of exceptional fearsome-Terror,

Powerful Ninurta!

Rising Hurricane,

Mighty possessor of august strength!

From whose grasp,

No Enemy/Aggressive lands escape!

Fitted for Heroism from the Womb

Unrivaled!

<<< - * - >>>

From Sumer Unto Islam

From El To Al-El.ah (Allah)

Sacred Figure & Paradigm Shifts:

Ninurta / Mardukh (Al-Maarid) / Mikha-El (Michael)

(1)

Ninurta

(Sumerian)

Perceptual Paradigm: Cosmos.

Mode of Communication/Expression: Symbols.

Perceiving Faculty: Soul.

Perceptual Data Processing: Psych(e)ological.

Seat of Polity: Temple.

(2)

Mardukh

(Babylonian / Post-Sumerian 1)

Perceptual Paradigm: Mythos.

Mode of Communication: Poetry.

Perceiving Faculty: Heart.

Perceptual Data Processing: E-motional.

Seat of Polity: Camp.

(3)

Mikha-El / Meekaal

(Abrahamic / Post-Sumerian 2)

Perceptual Paradigm: Logos.

Mode of Communication/Expression: Prose.

Perceiving Faculty: Mind.

Perceptual Data Processing: Mental.

Seat of Polity: Palace.

(4)

” . . . . ”

"Blank / No Name / No Revelation"

( Post-Sumerian 3 )

Perceptual Paradigm: Chaos.

Mode of Communication: Techné.

Perceiving Faculty: Body.

Perceptual Data Processing: Physical.

Seat of Polity: Market.

Paradigm Shifts:

(1)

Cosmos/Age of Gold

(2)

Mythos/Age of Silver

(3)

Logos/Age of Bronze

(4)

Chaos/Age of Iron

* * *

Perception here is Aesthesis in its original Greek sense. English does not do it justice. The same with Psyche, Cosmos et cetera.